A New Approach to Organization Design

In a time of economic turbulence, disruptive technology, globalization, and unprecedentedly fierce competition, the priority concern for many business leaders is to adapt to the changing conditions in order to boost their company’s performance. For that purpose, they frequently turn to organization design for help. By driving a thorough organizational review and redesign, company leaders can change the trajectory of their business.

Corporate reorganization is certainly in vogue. In a survey conducted by The Boston Consulting Group, almost 80% of respondent companies reported under-going a recent reorganization exercise—in about half of those cases, a large-scale, enterprise-wide reorganization initiative.

If only it were that easy. The results have been disappointing: survey respondents rated fewer than half of the reorganization efforts as successful. The underlying reason for such a low success rate: all too often, the companies’ leaders relied on organizational frameworks that have become outmoded and ineffective in today’s business environment.

THE TRADITIONAL APPROACHES: HARD AND SOFT

In grappling with organization design, company executives tend to draw on two venerable approaches, which can be characterized as the “hard” approach and the “soft” approach.

The hard approach can be traced back more than a century to the pioneering work of Frederick W. Taylor on the subject of scientific management. The approach rests on two broad assumptions: first, that performance is affected directly and crucially by structures, processes, systems, and financial rewards; second, that people’s behavior is something to be controlled—through structures, processes, and systems and by offering financial incentives based on performance metrics.

Because performance levels often seemed curiously resistant to the hard approach and the level of control achieved was limited, organizational theorists began supplementing it with the soft approach. This approach involves encouraging positive attitudes and interactions among the workforce by means of team-building activities, workshops emphasizing values, and other “people initiatives.” It can be traced to the work of Elton Mayo in the 1920s and the subsequent human relations school of management. The new thinking was, very roughly, as follows: performance is heavily influenced by interpersonal relationships, which are largely determined by mind-sets, which can be changed—not by financial incentives but by improved communication and emotional and social reassurance. The underlying purpose here, as with the hard approach, is control. The main difference is that the mechanism used to achieve it is psychological rather than economic.

Both approaches underplay the importance of individual autonomy and rationality. First, people are less likely to behave in the way we want if coerced or manipulated into such behavior than they are if the choice is their own. (And in any case, the kind of work they now generally do is not really amenable to control: in a knowledge economy, workers need to apply their own judgment rather than simply follow a set of rules.) Second, workers—being rational—act in their perceived own best interests. So, the modern approach to organization design should not be to seek control but rather to create the right context for the workforce, by aligning their own best interests with the mission of the organization. Once that context is suitably conducive, the workers will change their behavior of their own accord and will act together, as a team, to carry out the organization’s mission.

(This account is adapted from the book Six Simple Rules: How to Manage Complexity without Getting Complicated, by Yves Morieux and Peter Tollman, Harvard Business Review Press, 2014.)

A Call to Action

The business world of the early 21st century is radically different from that of the early 20th century, in two key respects.

First, organizations now have to operate in a vastly more complex environment—one of globalization, hypercompetition, revolutionary technologies, and elaborate regulation. Such complexity implies an increased number of performance requirements for companies (for instance, to satisfy customer needs, address competitive pressures, or comply with the ever-increasing labyrinth of regulation). If you then assign to each requirement its own structural solution (which is the essence of the “hard approach,” described in the sidebar) you end up with an extremely complicated and unwieldy organization.

Second, in most companies the nature of work has changed: from algorithmic work—that is, clerical or manual labor—to knowledge or heuristic work. Knowledge workers differ from clerical or manual workers in that their role is not merely to follow rules and perform specific tasks but also to use their own initiative to further the organization’s mission. They have to interpret the rules, adjust to the changing realities, and make trade-offs among conflicting requirements in order to arrive at the optimal solution.

All of that requires judgment. Judgment in turn involves creativity and full engagement on the part of the workforce. For algorithmic work (and in the hard approach to organization design), variation is discouraged and minimized—people need to follow the rules. Knowledge work and creative engagement, however, actually embrace variation and flourish in proportion. What’s more, heuristic workers on the front line, in order to make the most reliable and creative judgments possible, must master and monitor local conditions. So, in this respect, they are now the experts: they know more about this aspect of the trade-offs than their superiors do and, accordingly, need greater autonomy and empowerment.

If reorganization efforts continue to overlook these two major changes in the world of work, they will continue to fail. A new approach is needed, one that is better suited to the realities of the world in which companies now operate. BCG has developed such an approach, called Smart Design for Performance—or just Smart Design—drawing on the principles of Smart Simplicity. (See “Smart Design, Smart Simplicity.”) The approach has been battle tested and has shown great success in raising company performance, mastering complexity, and enhancing employee engagement.

SMART DESIGN, SMART SIMPLICITY

Smart Design is based on BCG’s Smart Simplicity model of how to design organizations for performance. Two of the framework’s key tenets are as follows:

A company’s performance is a direct consequence of its people’s behavior, which in turn is a response to the contexts in which these people find themselves. The performance of any organization is driven by the behaviors of the individuals in that organization: the decisions they make, the activities they undertake, and their interactions. These behaviors are rational—a rational reaction to a particular situation; they are not “hyper-rational,” as the behaviors of a computer algorithm might be. Rather, they represent the individuals’ perceived best strategy in the situation. To change these behaviors, and hence raise the organization’s performance level, you have to make a new set of behaviors rational; to do that, you have to change the situation, or context.

The new context must encourage cooperation. Company performance improves strongly when organizations raise the level of cooperation among the individual actors and align individual goals more closely with company goals. Cooperation, in this sense, occurs when one individual takes action to improve the performance of another; it brings synergy, such that everyone’s efforts combine in the most effective way and benefit the whole group. Cooperation is therefore the essence of teamwork; the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

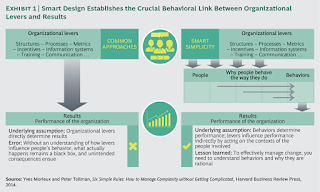

The Basis of a New Approach

A holistic view of organization design would encompass numerous components: structural elements, roles and responsibilities, individual talent, and enabling mechanisms such as core enterprise decision-making processes, performance management, and talent management. These are the key levers for organizational change, and they are obviously crucial—but their relevance is indirect. To change a company’s performance is to change what happens in the company. And what happens in a company is not directly a matter of organizational levers (such as structures, processes, and systems) but one of behavior—that is, what people do: how they act, interact, and make decisions. Workforce behavior is what determines company performance.

All of the various organizational levers act together to affect behavior, and that in turn affects company performance. But the traditional approaches assume, incorrectly and damagingly, that the organizational levers act directly and proportionately on company performance.

(See Exhibit 1.)

View enlarged imageThe new approach to redesigning an organization, far more appropriate for the new business environment, has behavior at its core. It involves identifying and explaining the current behaviors of the workforce, defining the desired behaviors—those that would improve company performance—and generating the new behaviors by creating contexts that are conducive to them.

What’s So Smart About Smart Design?

BCG’s Smart Design approach involves three main steps—the why, what, and how (see Exhibit 2):

- Define the purpose of the reorganization (the why).

- Determine the behaviors that will support that purpose and design the organization in such a way as to promote those behaviors, using a broad range of design elements (the what).

- Make it happen (the how).

Define the Purpose of the Reorganization

By redesigning the organization, your company can resolve many stubborn issues of strategy and execution. But before embarking on the redesign, make sure to identify clearly the company’s current performance shortfall (that is, the gap between the company’s current performance and its target performance) and hence the precise aims of the reorganization effort—with regard to competitive advantage, strategic priorities, or organizational pain points.

There are various ways to approach such an assessment. (For a summary of one of them, see “BCG’s Complicatedness Survey.”)

BCG’S COMPLICATEDNESS SURVEY

Organizations today operate in an environment of unprecedented complexity, owing to factors such as competitive intensity, globalization, high technology, tighter regulation, and customer empowerment.

But that does not mean that the organizations themselves have to be characterized by complicatedness—by having needless KPIs or excessive managerial layers, for example. Complicatedness is a consequence of misguided organization design. Whereas complexity can be a source of advantage if managed effectively, complicatedness impairs the functioning of an organization by restricting management’s agility and reducing the workforce’s engagement.

BCG has developed a complicatedness survey for client organizations. The online survey contains a standardized set of questions to gauge not just the overall level of complicatedness in an organization but also the specific level of each of seven context dimensions. And it captures not just the facts but—almost equally important—the beliefs or perceptions of key stakeholders. By highlighting the organizational pain points in this way, the survey helps to identify the aspects that would most benefit from redesign. (See the exhibit below.)

Determine the Target Behaviors and Design the Organization Accordingly

In this second step, you define the behaviors required to achieve the purpose. That will, in turn, lead to a set of design principles to be used for guidance as you shape the four key design elements, which are the building blocks for producing the desired behaviors. These elements are organizational structure, roles and responsibilities, individual talent, and organizational enablers. Note that they affect one another in many ways, and they act in combination to alter the context for individuals and encourage behaviors that drive high performance. So, instead of dealing with each of the four elements independently, you need to consider them jointly and align them.

Organizational Structure. Organizational structure refers to the hierarchy of management reporting—who reports to whom with regard to executing the strategy. These reporting lines establish the organization’s geometry: the spans of control and the number of layers.

Organizational structure can affect behavior profoundly. That is because the reporting relationship is an important basis of power: a line manager has power over his or her subordinates by virtue of being able to influence things that matter to them—notably, their assignments, remuneration, and career paths.

“Power and Related Concepts.”

Cooperation is the essence of teamwork: it involves more than just collaboration and coordination; it consists of behavior by individuals that increases the effectiveness of a group in pursuit of a shared goal. When you as an individual cooperate, you take into account—in your decisions and your actions—the needs and situations of your colleagues, rather than simply pursuing your own preferences.

Cooperation is not as easy as it sounds, nor as common. Don’t assume that it happens automatically in your organization. Individuals are, by nature, self-interested and value their autonomy, so they often resist cooperation, because it requires a personal sacrifice, or adjustment cost, from them. This adjustment cost might be professional, emotional, reputational, or, of course, financial.

If an individual avoids cooperating by refusing to make the adjustment cost, then the cost is incurred elsewhere—by others in the team or organization (in the form of underperformance, perhaps), or by the team or organization as a whole (in the form of lower productivity), or by people external to the organization—such as customers (through defects, delays, or higher prices) or shareholders (through lower returns).

An important way to secure cooperation within a group is for the group leader to exercise leadership (that means getting people to do things that they wouldn’t do spontaneously) and for that purpose, he or she needs appropriate power (power rather than just status).

Power can be defined as influence over things that are important to others: it is not necessarily correlated to one’s position in the hierarchy. A line manager coordinating a large project, for example, will have power over direct reports (via influence over their salaries or promotion prospects) but not necessarily over nondirect reports, and so might be unable to secure cooperation among them—a sure sign of a dysfunctional organization and the need for an organization redesign or at least an adjustment.

In any team or company, the work done by one person affects the ability of others to do what they have to do. That creates interdependencies. And interdependencies create a need for cooperation.

Cooperation is the essence of teamwork: it involves more than just collaboration and coordination; it consists of behavior by individuals that increases the effectiveness of a group in pursuit of a shared goal. When you as an individual cooperate, you take into account—in your decisions and your actions—the needs and situations of your colleagues, rather than simply pursuing your own preferences.

Cooperation is not as easy as it sounds, nor as common. Don’t assume that it happens automatically in your organization. Individuals are, by nature, self-interested and value their autonomy, so they often resist cooperation, because it requires a personal sacrifice, or adjustment cost, from them. This adjustment cost might be professional, emotional, reputational, or, of course, financial.

If an individual avoids cooperating by refusing to make the adjustment cost, then the cost is incurred elsewhere—by others in the team or organization (in the form of underperformance, perhaps), or by the team or organization as a whole (in the form of lower productivity), or by people external to the organization—such as customers (through defects, delays, or higher prices) or shareholders (through lower returns).

An important way to secure cooperation within a group is for the group leader to exercise leadership (that means getting people to do things that they wouldn’t do spontaneously) and for that purpose, he or she needs appropriate power (power rather than just status).

Power can be defined as influence over things that are important to others: it is not necessarily correlated to one’s position in the hierarchy. A line manager coordinating a large project, for example, will have power over direct reports (via influence over their salaries or promotion prospects) but not necessarily over nondirect reports, and so might be unable to secure cooperation among them—a sure sign of a dysfunctional organization and the need for an organization redesign or at least an adjustment.

The overall architecture of a company tends to reflect the company’s priorities. If the priority is functional excellence, for instance, then the company will usually be organized functionally; if the priority is customer intimacy, then the company will likely be structured according to customer type.

The problem is that almost all companies need to address multiple, often conflicting, priorities in order to be competitive in today’s environment. For example, in a functional organization, the emphasis might still be on serving customers or on organizing optimally to develop new products. Structure alone is not the answer. If a company neglects other ways of influencing behavior, and concentrates on making multidimensional or overly sophisticated structural changes (or just continues to add new structures) in order to cater to its conflicting priorities, the result is complicatedness and extra bureaucracy. Which is where Smart Design comes to the rescue.

Another way that organizational structure affects behavior is through geometry: the more layers the structure accommodates, the longer the chain of command becomes, and that can have counterproductive consequences—slower decision making, managers hampered by an overly narrow span of control, a tendency for units to work in silos, and uncooperative or disruptive behaviors by frustrated workers.

The trend in recent decades has been for organizations to reduce the number of layers within their hierarchies. Yet overlayering persists, for two reasons.

First, the layers are often generated as a reflex response to business complexity: if a growing company opts to create a new regional structure, for instance, it would understandably be tempted to create a new layer in the organizational hierarchy to accommodate the regional heads.

The second possible reason is that if the organization is poor at inspiring its workforce to perform, it might overuse a particular incentive: the prospect of promotion. New layers might then be needed to accommodate the various employees who are being “rewarded” in this way. The new positions seldom add much value, and the roles involve little or no power. The effects of these extraneous layers and narrow spans of control include slower decision making, silo behavior, and subdued productivity.

In contrast, a smart and effective organization is lighter and flatter in structure, allowing for flexibility and agility. It specifies fewer and bulkier management roles with broad spans of control and motivates the employees in those roles to use their own initiative and to exercise their creativity in finding solutions.

Roles and Responsibilities. Roles and responsibilities clarify who does what and who is accountable for what. For the staff to adjust their behavior in a more cooperative direction, they need to understand their own responsibilities and those of their colleagues. They also need to know how these responsibilities are to be discharged, what decision rights and key capabilities are needed, and how to measure success. To foster performance and cooperation, the roles and responsibilities should be sharply focused on what matters most; they should be defined more in terms of the what than the how; and there should be sufficient overlap to ensure that all the bases are covered but not so much overlap that work would be duplicated or rivalries would emerge.

An effective way to design roles and responsibilities is through the process of “role chartering.” Each role is defined—on a single sheet of paper each time—in six related aspects:.Desired leadership markers for the role—the values, characteristics, and “style” best suited to the role, such as a bias toward action, a sense of urgency, or candor and openness.

The charters, if effectively designed, will help to foster cooperative behaviors and add value accordingly.

The challenge is not just to define a person’s independent responsibilities but also to define his or her shared responsibilities with regard to the work of others, in light of interdependencies. So too for metrics: how is success to be measured? (If you cannot measure it accurately, you cannot reward it appropriately, and if you cannot reward it appropriately, you cannot easily incentivize people to engage in it. The metrics might show that each silo is performing strongly, while the performance of the organization as a whole might be weak.) Cooperation cannot be measured, at least directly or quantitatively—hence the need for managerial supervision of key interactions and for spelling out the mission-critical cooperation requirements.

The key is to align the charters of those people who especially need to cooperate with one another. If your own role charter, thanks to a systematic alignment process, chimes well with those of your supervisors and your peers, that should both clarify individual and shared accountabilities and facilitate productive and cooperative behavior.

Note again the important role played here by power (that is, influence over things that are important to others). It is power that determines your capacity for gaining cooperation from others and hence for dealing with business complexity. One way for a company to empower you is by incorporating into your role charter a new “stake” for others (something that matters to them). Suppose, for example, that your role charter authorizes you to select various colleagues for a desirable task or to submit an assessment report on them to their line manager when their promotion prospects come under review: in each case, your role charter is empowering you—these colleagues would now have an incentive to listen to you and cooperate with you, and you would be in a position to influence their behavior. Or suppose that your role charter gives you the decision right over a policy that some of your colleagues wish to introduce or over budget allocations for a project of theirs: again, that would serve as an extra source of power for you, encourage cooperation from your colleagues, and make it easier for you to fulfill your shared accountability.

All in all, by devising role charters for key positions in the organization, a company can accomplish several aims: clarify the individual and shared accountabilities, establish how to align roles and responsibilities horizontally and vertically with the desired behaviors, secure from everyone involved the necessary buy-in for behavioral change, and increase power and alignment in the organization, in order to enhance autonomy and cooperation and thereby cope better with complexity.Individual Talent. Individual talent is needed for filling the roles and discharging the responsibilities. To be a good match for a given role, the individual obviously must have (or be able to acquire) the right skill set and the motivation. That way, the role is performed effectively, the individual is engaged rather than disaffected, and the individual’s colleagues are therefore undistracted and likely to behave productively and not disruptively.

To achieve the right match, proceed in a methodical way. Begin by reviewing each key role and specifying the talent it needs; then choose the most promising candidate, regardless of current seniority, salary level, or contract type (external resourcing is one of the options).

If necessary, the company will aim to “upskill” the candidate for a new role, via mentoring, training, or other development opportunities. This upskilling is particularly important around the time of a reorganization effort. Consider the example of a senior role holder: during preparations for the reorganization, he or she might need to learn new ways of designing a team or of managing difficult conversations. And after the reorganization has taken place, he or she might need to acquire new managerial skills in such areas as leading a new team, resolving conflicts across units, and managing a broader span of control. Once equipped with the appropriate talent or skill sets again, the role holder is in a position to fulfill his or her new responsibilities.

However, that might still not be enough. The individual also needs the motivation to apply these skills, specifically in a cooperative way. When companies are struggling to execute a strategy, they often lay the blame on skill gaps when the real culprit is rather different: a shortage of cooperation. The solution is to make adjustments to the context, in such a way that a committed fulfillment of the responsibility becomes a rational and personally beneficial behavior for the role holder.

Any new organization design should not only deploy and leverage existing talent to the full but also aim to attract, retain, and develop future talent. One strategy in this regard is to create and foster roles that offer great learning experiences or enhanced career paths. Once again, make sure to create a conducive context for such roles—one that gives an ambitious and talented individual the right amount of exposure, for example, and provides him or her with the right opportunities to move on after a while.

Organizational Enablers. Finally, organizational enablers provide further help in creating the coherent organizational context that encourages the desirable behaviors. The main enablers are enterprise-level decision processes and their support systems, performance management, and talent management.

Among the enterprise-level decision processes are strategic planning, product and portfolio planning, budget allocation, and major capital investments. Decision making within organizations often becomes slow and contentious, and when a company tries to improve the situation by imposing formal guidelines and new processes, it often just complicates things and makes matters worse.

Once again, the right approach is to create a conducive context: the major stakeholders can then cooperate with one another to generate effective and timely decisions for the company’s benefit. As an additional resource for sharpening their decision-making abilities, the stakeholders have access to a support system, including IT platforms and data analytics. This system needs to be well designed, however, and the analytics need to be relevant as well as practical. Failing that, the system could actually prove counterproductive, and weaken rather than strengthen the quality of decisions made within the organization.

Performance management is conducted through staff evaluations. The evaluations would ideally involve a combination of KPIs and judgment-based assessments. The company should ensure that those conducting the performance management are properly equipped to do so. They need to acquire the requisite skills, by means of training, if necessary—how to recognize cooperative and uncooperative behaviors, for instance, or how to provide feedback candidly but constructively.If executed well, performance management can help to enhance workplace behavior—but it is liable to misuse. All too often, companies deploy performance assessment criteria to link operational failures to specific roles or individuals. The clearer the link, the more strongly the company believes it has the right assessment system—only to find that these direct attributions have the effect of making matters even worse and prompting suboptimal or even counterproductive behavior. A smart organization understands that performance requirements can be highly complex and often conflicting and accepts that problems of execution arise for many reasons. It also understands that frequently the best way to solve these problems is to increase cooperation, and that means reducing the payoff for those people or units engaging in uncooperative behavior, even if the problem does not take place directly in their own domain, and to increase the payoff for everyone when everyone cooperates in a beneficial way.

As for talent management (through appointments, promotions, or a new career path, for example), it too can have a powerful effect on the way that people behave. One technique is to carefully assign people the role—perhaps as a temporary transfer—of someone affected by their behavior. By getting them to walk in another’s shoes in this way, you alert them to the “shadow of the future”—that is, you make them aware of the problems that their current behavior might create for their future selves. This technique is particularly effective when the outcomes of their behavior lie very far in the future. (In biopharma R&D, for example, the time lag between decision and outcome is so great that the decision maker might never be personally affected by the outcome.) By reminding people that what happens tomorrow is a consequence of what they do today and making them accountable for it, you give them an incentive to optimize their current behavior.

Both performance management and talent management need careful designing to create the right context for behavior. It is all too easy to misalign them with target behaviors and thereby actually encourage the counterproductive behaviors that you are setting out to eradicate.

Make It Happen

Reorganization is undertaken not for its own sake but in order to successfully execute strategy and boost performance (in each case, by modifying the behavior of the workforce). So the implementation phase is crucial. It has two main aspects: establishing the right context throughout and enhancing the capabilities of leaders and top talent. And it can be accomplished most efficiently through a process with three features: cascaded design, rigorous program management with multilayered communication, and capability building.

Cascaded design, or “layer-by-layer, team-by-team design,” involves role chartering by each employee successively down the organization, in consultation with his or her colleagues and line manager. This cascading process helps to refine and publicize each role—clarifying the interdependencies and the way they affect one another—as well as speeding up decision making and reinforcing strategic goals throughout the organization.

Rigorous program management involves creating, tracking, and course correcting a portfolio of change initiatives. If conducted properly, it maximizes the visibility of the change program and ensures that members of the workforce understand and feel the consequences of their actions. Through feedback loops, it indicates, encourages, and reinforces the desired behaviors. One of its major components is multilayered communication—at all levels of the hierarchy, senior managers hold one-on-one conversations with their subordinates and conduct pulse checks or surveys to monitor how their subordinates are progressing and how they feel. In that way, they can gain insights into the effects of the new context and make adjustments to it as needed.

Capability building, or enablement, drives performance and hence value. Organization design provides a unique opportunity for companies to boost capabilities in this way, provided that the company’s leaders and top talent learn the necessary skills: first, how to execute the organization redesign smoothly, then how to lead within the new organizational context and help their subordinates to adapt, and then how to drive business objectives and value in their new roles. To ensure sustainable outcomes in each of these requisites, companies often benefit from a tailor-made leadership- and talent-development program.

When it comes to applying Smart Design to actual situations, the details obviously differ from case to case, according to the purpose of reorganization, its scope and scale, and the company’s current organizational capabilities. Some reorganization initiatives clearly need all three components of the enhanced organization-design program; for others, just one or two of the components might be enough. (For two instructive case studies, see “Smart Design in Action.”)

SMART DESIGN IN ACTION

Two case studies provide insight into the power of the Smart Design approach.

Making a New LoB-and-Hub Matrix Work

A multibillion-dollar financial institution in the US was underperforming, and a serious reorganization was indicated. A redesign initiative duly got under way, with the aim of transitioning the organization from a predominantly line-of-business

(LoB) structure to a matrix of LoBs and hub centers. The upshot was exacerbation of the drivers of underperformance:

⦁ Decision making became slower and more contentious.

⦁ Cross-functional efforts proved increasingly disappointing.

⦁ The brand LoBs avoided collaborating with the hubs, citing various concerns involving the hubs’ capabilities and processes.

⦁ Talent development continued to deteriorate.

When BCG was invited to help resolve these issues, our Smart Design team began by analyzing exactly what was happening and why. The team studied the key actors, identified the undesirable behaviors, and established why those behaviors were rational in the given context. The team then developed a suite of solutions that would make a new set of behaviors rational—that is, more cooperative and productive. Finally, the team developed a change program for implementation.

The company was then able to resume its redesign initiative, but on a proper footing this time. It redefined roles and revised the rewards system in such a way as to reinforce the hubs and attract the right talent to the right positions. Further effects included reduced waste, increased cooperation, clearer accountability, higher levels of employee engagement—and overall improved performance.

Thanks to the quick course correction, a reorganization effort that had been heading for the rocks was diverted into a favorable current, and the company’s prosperous voyage continues.

Fixing the Issues Affecting New CoEs

In a major strategic initiative, a global chemical company embarked on a radical reorganization: the old structure, which was based on business units, was to be replaced by a new matrix structure, with centers of excellence (CoEs) for key shared functions such as analytics, customer insights, marketing excellence, and sales operations. The goal was twofold: to improve efficiencies by building scale in these areas and to boost capabilities to the point of excellence.

To the transformation team’s surprise, the new organization design floundered. The twin goals seemed further away than ever.

The broad problem was that in creating the CoEs, the company had pressed the structural levers but neglected all the other levers. Roles and responsibilities remained unclear. The talent assigned to the CoEs was ill considered—generalists rather than appropriate specialists. And the talent management was poorly conducted: career paths were considered “second class,” turnover was high, and top performers refused to transfer from brand teams to CoEs.

In short, redesign had not been accompanied by corresponding changes to the context.

With BCG’s support, the company set about mapping clearer career paths for those assigned to the CoEs, redefining and rechartering roles to make them more compelling, clarifying decision rights, and adjusting the mix of staff in order to generate real expertise within teams. Within three months of the “redesign of the redesign,” employees registered a hugely improved understanding of their roles and a general rise in satisfaction.

Subsequent assessments have shown that the organization is now much more scalable, and performance is markedly higher than before.

As mentioned earlier, BCG conducted a survey on reorganization, polling corporate executives in a wide range of industries. The survey identified six factors as the strongest contributors to the success of reorganization efforts: aligning design with strategy, clarifying roles and responsibilities, deploying the right leaders and the right capabilities, designing layer by layer (not just from the top down), executing optimally by minimizing risk factors, and reorganizing during a period of strength rather than crisis. The findings of the survey were illuminating, to say the least: companies that embraced all six success factors within their reorganization effort enjoyed vastly greater success than companies that did not. With each additional factor, the success gained further impetus. (See Exhibit 3.) Subsequent case experience has confirmed the importance of these factors.

![]()

These findings are consistent with our expectations. In Smart Design, the emphasis is less on perfecting each element and more on creating the context in which the elements can work most effectively together to drive the target behaviors and enhance performance. So, when business leaders commit to an organization redesign, they should take a holistic approach rather than treat each factor individually. (For a more detailed account, see Flipping the Odds for Successful Reorganization, BCG Focus, April 2012.)

Smart Design is premised on the recognition that company performance is a function of employee behavior. So to improve performance, the trick is to modify behaviors appropriately. And to do that, you must first study the existing behaviors—the good, the bad, and the absent—and then comply with the other success factors listed in the middle column of Exhibit 3. As the final column shows, a conscientious approach to reorganization can make a striking difference to its chances of success.Successful reorganization is often the most promising route for companies to regain their former sparkle, consolidate their strengths, or gain a competitive advantage. But taking that route requires steady nerves and bold measures. Many corporate executives are sufficiently bold to authorize a thoroughgoing organization redesign, but not to break with the conventional approaches to it. The trouble is, the conventional approach has produced uninspiring results in recent years, and in many cases has actually made matters worse.

It is simply inadequate in the present-day business environment: the circumstances have changed, and the approach needs to change as well. To drive productive behaviors, you must create broader and more conducive contexts for them and then implant the new contexts, layer by layer, deeply into the organization. Smart Design is a comprehensive end-to-end approach that is specifically adapted to the new circumstances and precision-engineered for boosting performance and engagement. It has produced outstanding results with minimal disruption: companies applying Smart Design have seen a revival of employee motivation and engagement and a surge in company performance. If reorganization initiatives often offer the best hope for troubled companies, Smart Design offers the best hope for reorganization initiatives.

AAI Jr Executive Recruitment 2016: The CTC would be around Rs 6.9 lakh.

AAI Jr Executive Recruitment 2016: The CTC would be around Rs 6.9 lakh.

Cooperation is the essence of teamwork: it involves more than just collaboration and coordination; it consists of behavior by individuals that increases the effectiveness of a group in pursuit of a shared goal. When you as an individual cooperate, you take into account—in your decisions and your actions—the needs and situations of your colleagues, rather than simply pursuing your own preferences.

Cooperation is not as easy as it sounds, nor as common. Don’t assume that it happens automatically in your organization. Individuals are, by nature, self-interested and value their autonomy, so they often resist cooperation, because it requires a personal sacrifice, or adjustment cost, from them. This adjustment cost might be professional, emotional, reputational, or, of course, financial.

If an individual avoids cooperating by refusing to make the adjustment cost, then the cost is incurred elsewhere—by others in the team or organization (in the form of underperformance, perhaps), or by the team or organization as a whole (in the form of lower productivity), or by people external to the organization—such as customers (through defects, delays, or higher prices) or shareholders (through lower returns).

An important way to secure cooperation within a group is for the group leader to exercise leadership (that means getting people to do things that they wouldn’t do spontaneously) and for that purpose, he or she needs appropriate power (power rather than just status).

Power can be defined as influence over things that are important to others: it is not necessarily correlated to one’s position in the hierarchy. A line manager coordinating a large project, for example, will have power over direct reports (via influence over their salaries or promotion prospects) but not necessarily over nondirect reports, and so might be unable to secure cooperation among them—a sure sign of a dysfunctional organization and the need for an organization redesign or at least an adjustment.