Slowly but steadily, it’s dawning on Western multinationals that it may be a good idea to design products and services in developing economies and, after adding some global tweaks, export them to developed countries. This process, called “reverse innovation” because it’s the opposite of the traditional approach of creating products for advanced economies first, allows companies to enjoy the best of both worlds. It was first described six years ago in an HBR article co-written by one of the authors of this article, Vijay Govindarajan. (See “How GE Is Disrupting Itself,” October 2009.)But despite the inexorable logic of reverse innovation, only a few multinationals—notably Coca-Cola, GE, Harmon, Microsoft, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Procter & Gamble, Renault, and Levi Strauss—have succeeded in crafting products in emerging markets and selling them worldwide. Even emerging giants—such as Jain Irrigation, Mahindra & Mahindra, and the Tata Group—have found it tough to create offerings that catch on in both kinds of markets.

For three years now we’ve been studying this challenge, analyzing more than 35 reverse innovation projects started by multinationals. Our research suggests that the problem stems from a failure to grasp the unique economic, social, and technical contexts of emerging markets. At most Western companies, product developers, who spend a lifetime creating offerings for people similar to themselves, lack a visceral understanding of emerging market consumers, whose spending habits, use of technologies, and perceptions of status are very different. Executives have trouble figuring out how to overcome the constraints of emerging markets—or take advantage of the freedoms they offer. Unable to find the way forward, they tend to fall into one or more mental traps that prevent them from successfully developing reverse innovations.

Our study also shows that executives can avoid these traps by adhering to certain design principles, which together provide a road map for reverse innovation. We distilled them partly from our work with multinationals and partly from the firsthand experiences of a team of MIT engineers led by this article’s other author, Amos Winter. His team spent six years designing an off-road wheelchair for people in developing countries, which is now manufactured in India. Called the Leveraged Freedom Chair (LFC), it is 80% faster and 40% more efficient to propel than a conventional wheelchair, and it sells for approximately $250—on par with other developing world wheelchairs. The technologies that generate its high performance and low cost have been incorporated into a Western version, the GRIT Freedom Chair, which was modified with consumer feedback and sells in the United States for $3,295—less than half the price of competing products.

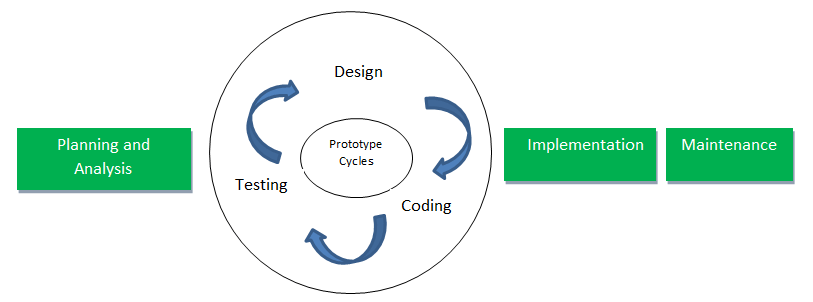

As we will show in the following pages, the reverse innovation process succeeds when engineering creatively intersects with strategy. Companies can capture business opportunities only when they design appropriate products or services and understand the business case for them. That’s why it took two academics—one teaching mechanical engineering, and the other strategy—to come up with the principles that must guide the creation of reverse innovations.

Five Traps—and How to Avoid Them

For every product, multinational companies typically produce three variations: a top-of-the-line offering, which provides the best performance at a premium price; a “better” version, which delivers 80% of that performance at 80% of the price; and a “good” variant, which provides 70% and costs 70% as much. To break into emerging markets, where consumers have very high expectations but much smaller pocketbooks, multinationals usually follow a design philosophy that minimizes the up-front risks: They value-engineer the “good” product, watering it down to a “fair” one that offers 50% of the performance at 50% of the price.

This rarely works. In developing countries, not only do “fair” (or “good enough”) products prove too expensive for the middle class, but the upmarket consumers—who can afford them—will prefer the top-of-the-line versions. Meanwhile, because of economies of scale and the globalization of supply chains, local companies are now bringing out high-value products, at relatively cheap prices, more quickly than they used to. Consequently, most multinationals capture only small slivers of the local market.

To win over consumers in developing countries, multinationals’ products and services must match or beat the performance of existing ones but at a lower cost. In other words, they must provide 100% of the performance at 10% of the price, as product developers wryly put it. Only through the creation of such disruptive products and technologies can companies both outperform local rivals and undercut them on price. But the traps we mentioned earlier prevent companies from meeting this challenge. To escape those traps, they must follow five design principles.

Trap 1: Trying to match market segments to existing products.

Current offerings and processes cast a long shadow when multinationals start creating products for developing countries. At first it appears to be quicker, cheaper, and less risky to adapt an existing product than to develop one from scratch. The idea that time-tested products, with modifications, won’t appeal to lower-income customers is difficult to digest. Designers struggle to get away from existing technologies.

The U.S. tractor-manufacturer John Deere, a seasoned global player, encountered this problem in India. There Deere initially sold tractors it had carefully modified for emerging markets. But its small tractors had a wide turning radius, because they had been designed for America’s large farms. Indian holdings are very small and close to one another, so farmers there prefer tractors that can make narrow turns. Only after John Deere designed ab initio a tractor for the local market did it taste success in India.

Design Principle 1: Define the problem independent of solutions.

Casting off preconceived solutions before you set down to define problems will help your company avoid the first trap—and spot opportunities outside its existing product portfolio. Consider the problem of irrigating farms in emerging markets. Farmers will argue for the expansion of the power grid so that they can use electricity to run water pumps and irrigate fields. However, farmers need water, not electricity, and the real requirement is getting water to crops—not power to pumps. If they isolate the problem, engineers may find that creating ponds near fields or using solar-powered pumps is more cost-effective and environmentally appropriate than expanding the power grid.

When defining problems, executives must keep their eyes and ears open for behavior that may signal needs that customers haven’t articulated. In 2002, Commonwealth Telecommunications Organisation researchers reported that in East Africa, people were transferring airtime to family and friends in villages, who were then using or reselling it. Doing so allowed workers in cities to get money to people back home without making long and unsafe journeys with large amounts of cash. It indicated a latent demand for money remittance services. That’s how M-Pesa, the successful mobile money-transfer service, was born.

It’s good to study the global market in-depth before kicking off the design process. For example, when the MIT team analyzed the wheelchair market, it learned that of the 40 million people with disabilities who didn’t have wheelchairs, 70% lived in rural areas where rough roads and muddy paths were often the only links to education, employment, markets, and the community.

Environmental conditions were harsh; traditional wheelchairs broke down quickly as a result and were difficult to repair. Because of their poverty, most people got wheelchairs free or at subsidized prices from NGOs, religious organizations, or government agencies. Those suppliers were willing to pay $250 to $350 for a wheelchair—an important price constraint.

No wheelchair user specified the mobility solution he or she desired; the team had to figure out the needs of the market by watching and listening. For inspiration, it drew on the numerous complaints it heard: Wheelchairs were tough to push on village roads; manually powered tricycles were too big to use indoors; imported wheelchairs couldn’t be repaired in villages; the commute to an office was often more than a mile, so it was tiring. And so on.

The team’s assessment of consumer needs generated four core design requirements:

1. A price of approximately $250

2. A travel range of three miles a day over varied terrain

3. Indoor usability and maneuverability

4. Easy, low-cost maintenance and local repair

Those criteria conveyed little about what form the wheelchair would have to take. However, had the team missed one of them, imposed an existing solution, or made its own assumptions, it probably would have failed.

Trap 2: Trying to reduce the price by eliminating features.

Many multinationals think this is the way to make products affordable for consumers in emerging markets. People in developing countries are willing to accept lower quality and products based on sunset technologies, runs the argument. This approach often leads to poor decisions and bad product designs.

For example, when one of the Big Three automobile makers decided to enter India in the mid-1990s, it charged its product developers in Detroit with coming up with a suitable model. The designers took an existing midprice car and eliminated what they felt were unnecessary features for India, including power windows in the rear doors. The new model’s price was within the reach of Indians at the top of the pyramid—who hire chauffeurs. Thus the chauffeurs got power windows up front while the owners had to hand-crank the rear windows, greatly reducing customer satisfaction.

Design Principle 2: Create an optimal solution, not a watered-down one, using the design freedoms available in emerging markets.

Though emerging markets have many constraints, they offer intrinsic design freedoms as well. These freedoms take various forms: In Egypt high irradiance makes solar power attractive in areas with unreliable power; in India low labor costs and high material costs make manual fabrication cost-effective. Even behavioral differences broaden companies’ options: Some African consumers prioritize the purchase of TV sets over roofs, suggesting that companies must appeal to users’ wants as well as their needs.

Carefully considering design freedoms helped the MIT team achieve many objectives. For instance, wheelchairs that use a mechanical system of multiple gears, just as geared bicycles do, were available in the developing world, but they were very expensive, and few could afford them. Compelled to devise an alternative, the engineers homed in on people’s ability to make a broad range of arm movements as something they could use in the drivetrain to make the chair go faster or slower. While that ability isn’t specific to emerging markets, the engineers wouldn’t have thought of using it if they weren’t trying to achieve high performance at a low price—a requirement specific to emerging markets.

The MIT team designed the LFC with two long levers that are pushed to propel the chair; users change speed by shifting the position of their hands on the levers. To go up a hill, users grab high on the levers and gain more leverage; in “low gear” the levers provide 50% more torque than pushing the rims of the chair does. On a flat road, they grab low and push through a larger angle to move faster, generating speeds that are 75% faster than a standard wheelchair’s. To brake, users pull back on the levers.

Products for emerging markets must provide 100% of the performance at 10% of the price.

By making the users the machines’ most complex part—they are both the power source and the gearbox—the team could fabricate the drivetrain from a simple, single-speed assembly of bicycle parts. In fact, the ability to use bicycle parts was another freedom the team could exploit. People in developing countries use bicycles extensively, and repair shops that stock spare parts are almost everywhere. Incorporating bicycle parts into the drivetrain made the LFC low cost, sustainable, and easy to repair, especially in remote villages.

Trap 3: Forgetting to think through all the technical requirements of emerging markets.

When designing offerings for the developing world, engineers assume they’re dealing with the same technical landscape that they are in the developed world. But while the laws of science may be the same everywhere, the technical infrastructure is very different in emerging markets. Engineers must understand the technical factors behind problems there—the physics, the chemistry, the energetics, the ecology, and so on—and conduct rigorous analyses to determine the viability of possible solutions.

Thorough calculations will allow engineers to validate or refute assumptions about the market. Consider the PlayPump, designed for Africa, which pumps water from the ground into a tower by harnessing the energy of village children pushing a merry-go-round. Having children do something useful for the community while playing is a win-win by any yardstick. Moreover, a first-order engineering analysis suggested that the technological assumptions were logical.

Let’s assume that in a 1,000-strong village, each person needs three liters of drinking water a day, the village has a tower that can hold 3,000 liters, and it’s 10 meters high. Using high school physics, one can calculate that 25 children, playing for 10 minutes each, could theoretically fill the tower.

But further analysis alters the picture. After all, children spin merry-go-rounds so that they can ride them until they’re dizzy, and if all the energy from their pushing goes to pumping water, the merry-go-round will stop as soon as they stop pushing. That’s no fun! If we assume that half their energy goes into spinning and half into pumping, the energy requirement doubles; 50 children must use the PlayPump for 10 minutes each daily to keep the tower full.

![]()

If the water comes from a well 10 meters deep, double the energy will be necessary and 100 children must use the merry-go-round. Accounting for inefficiencies, the number could go to 200. What happens when it’s too hot, wet, or cold, and children don’t want to play on the PlayPump? How will the village get its water then? If the makers of the PlayPump had included all those factors in their calculations, they would have realized it wasn’t a technically viable solution. Despite receiving the World Bank Development Marketplace award in 2000 and donor pledges of $16.4 million in 2006, PlayPumps International had stopped installing new units by 2010. The PlayPump sounded like a good idea, but a village water system needs reliable power—and ensuring that isn’t child’s play.

Design Principle 3: Analyze the technical landscape behind the consumer problem.

Underlying technical relationships may look markedly different in developing countries. For example, urban Indian homes receive water from pressurized municipal supply systems, just like those found in the United States, which ensure that if there is a leak, water goes out but contaminants can’t get in. However, most Indian households use booster pumps to suck water from the municipal pipes to rooftop tanks. This suction pulls contaminants from the ground into the pipes, creating a mechanism for contamination that is not common in the United States.

Social and economic factors often drive the technical requirements for products. For instance, if a company wants to sell inexpensive tractors to low-income farmers, it must make them light; material costs determine much of a tractor’s price. Engineers then must check how lowering the weight would affect the machine’s performance, particularly traction and pulling force. The latter is important; in emerging markets, farmers use tractors not only to farm but for odd jobs, such as transporting people.

By studying the technical landscape, engineers can identify pain points as well as creative paths around them. Understanding the requirements for energy, force, heat transfer, and so on will illuminate novel ways of satisfying them. As noted earlier, the LFC is human powered, which eliminates the costs of a motor and an energy source. However, the design team had to figure out how users’ upper body strength could provide propulsion. It did so by calculating the power and force that people could produce with their arms and the amounts needed on various kinds of terrain. Finally, the designers worked out the optimal length of the two levers so that users could travel at peak efficiency across normal terrain and have enough strength to propel their way out of trouble in harsh conditions such as mud or sand.

Trap 4: Neglecting stakeholders.

Many multinationals seem to think that all they need to do to educate product designers about consumers’ needs and desires is to parachute them into an emerging market for a few days; drive them around a couple of cities, villages, and slums; and allow them to observe the locals. Those perceptions will be enough to develop products that people will purchase, they assume. But nothing could be further from the truth.

Design Principle 4: Test products with as many stakeholders as possible.

Companies would do well to map out the entire chain of stakeholders who will determine a product’s success, at the beginning of the design process. In addition to asking who the end user will be and what he or she needs, companies must consider who will make the product, distribute it, sell it, pay for it, repair it, and dispose of it. This will help in developing not just the product but also a scalable business model.

It’s best to adopt the attitude that you’re designing with, not for, stakeholders. If treated as equals, they’re more likely to participate in the process and provide honest feedback. When you’re designing a prosthetic limb, for instance, collaborate with amputees, the clinics that provide the prostheses, and the organizations that pay for them. If you’re able-bodied, it doesn’t matter how many doctoral degrees you’ve earned; you still don’t know what it’s like to live with a prosthetic device in a developing country.

It’s not enough to parachute product designers into a market for a few days to observe the locals.

The MIT team formed partnerships with wheelchair builders and users throughout the developing world. Those stakeholders, who provided insights on how to make the wheelchair better, easier to manufacture, more robust, and cheaper, came up with ideas for several features. The team gathered further feedback through field trials in East Africa, Guatemala, and India, conducted in conjunction with local wheelchair manufacturing and supply organizations. The tests had a huge impact, resulting in several design modifications.

Although the first prototype performed well on rough terrain in East Africa, it didn’t do so well indoors. It was too wide to go through a standard doorway, which the MIT designers hadn’t noticed, and it was 20 pounds heavier than rival products were. For the next iteration, tested in Guatemala, the engineers reduced the chair’s width by shaping the seat closer to the user’s hips, bringing the wheels closer to the frame, and using narrower tires. By conducting a structural analysis, optimizing the strength-to-weight ratio of the frame, and reducing materials wherever possible, the team also decreased the LFC’s weight by 20 pounds. That version performed well indoors, but several users felt they might fall out when traversing rough terrain. So the team included foot, waist, and chest straps to secure the user to the seat in tests in India. Users rated the third version at par with conventional wheelchairs indoors and far superior outdoors.

No matter how thorough engineers are, users expose design flaws that only they can notice. For instance, of the seven major improvements users suggested, only eliminating the LFC’s excess weight had been evident to the MIT team before the East African trial. It’s critical to test prototypes in the field with potential users and design solutions with organizations that will disseminate the product. Remember, design is iterative; you can’t get it right the first time, so be prepared to test many prototypes.

Trap 5: Refusing to believe that products designed for emerging markets could have global appeal.

Western companies tend to assume that consumers in developed markets, who are brand-conscious and performance-sensitive, will never want products from emerging markets, even if their prices are lower. Executives also worry that even if those products did catch on, they could be dangerous, cannibalizing higher-priced, higher-margin offerings.

Design Principle 5: Use emerging market constraints to create global winners.

Before designing solutions, companies should identify the inherent constraints that will operate on the new product or service—such as low average consumer income, poor infrastructure, and limited natural resources. This list will dictate the requirements—like price, durability, and materials—that new designs must meet.

The constraints of developing countries usually force technological breakthroughs that help innovations crack global markets. The new products become platforms on which companies can add features and capabilities that will delight many tiers of consumers across the world. One example is the Logan, a car Renault designed specifically for Eastern European customers, who are price-sensitive and demand value. Launched in Romania in 2004, the Logan cost only $6,500 but offered greater size and trunk space, higher ground clearance, and more reliability than rival products. To ensure a low price, Renault used fewer parts than usual in the vehicle and manufactured it in Romania, where labor costs are relatively low.

Two years later, Renault decided to make the Logan attractive to consumers in developed markets, by adding more safety features and greater cosmetic appeal, including metallic colors. In France it sold the Logan for as much as $9,400. In Germany sales of the Logan jumped from 6,000 units to 85,000 units over a three-year period. By 2013 sales in Western Europe had reached 430,000 units—a 19% increase over 2012. Thus, while the constraints in Eastern Europe forced Renault to create a new auto design, the result was a product that delivered high value at low cost to consumers in Western Europe as well.

The constraints of developing countries usually force technological breakthroughs.

Something similar is happening with the LFC: Wheelchair users in the United States and Europe have noticed the media buzz about the product and want to buy it. The MIT team worked with Continuum, a Boston-based design studio, to conduct a study of what a U.S. version of the LFC could look like. The designers also tested the LFC with potential customers in the West to identify features to add. The GRIT Freedom Chair, as the developed world model is called, was designed to fit into car trunks in the United States. It also has quick-release wheels that users can remove with one hand and is made from bicycle parts available in the United States.

Although commercial production of the Freedom Chair began only in May 2015, it’s on its way to success in the developed world. The venture the MIT team founded to make the chairs, Global Research Innovation and Technology, was one of four start-ups that received a diamond award at MassChallenge, the world’s largest start-up competition, three years ago. In 2014, GRIT ran a Kickstarter campaign to launch the Freedom Chair, meeting its funding goal in only five days.

How the Principles Pay Off

Few companies have avoided the traps we’ve described as well as the global shaving products giant Gillette did when designing an offering for India. As recently as a decade ago, Gillette made most of its money in that country by catering to top-of-the-pyramid consumers with pricey products. In 2005, Procter & Gamble acquired Gillette and immediately saw an opportunity to expand market share in the country.

Prodded by its new parent, which had been in India since the early 1990s, Gillette decided to develop a product for the 400 million middle-income Indians who shave primarily with double-edge razors. It began by exploring consumer requirements. After mapping out the value chain, from steel suppliers to end users, a cross-functional team conducted ethnographic research, spending over 3,000 hours with 1,000 would-be consumers.

Gillette learned that the needs of Indian shavers differ from those of their developed world counterparts in four ways:

Affordability.

The price would be a critical constraint, since Gillette’s main competitor, the double-edge razor, costs just Re 1 (less than 2 cents).

Safety.

Consumers in this market segment sit on the floor in the dark early-morning hours and, using a small amount of still water, wield a mirror in one hand and a razor in the other. Shaving often results in nicks and cuts, because double-edge razors don’t have a protective layer between the blade and the skin.

Even so, when Gillette’s product designers watched Indian men shaving, most of the men did not cut themselves. Their response was simple: “We are experts; we don’t cut ourselves.” However, the team concluded that shaving requires concentration; Indian shavers could not relax or talk during the process for fear of injuring themselves. Gillette had identified a latent need: Most shavers were keen to relieve the tension by using a safer razor and blade.

Ease of use.

Indian men have heavier beards and thicker facial hair than most American men do, and shave less frequently, so they have to tackle longer hairs. They also like to use a lot of shaving cream. All of that leads their razors to clog up quickly. With little running water at their disposal, Indian men need razors that they can easily rinse.

Close shaves.

Gillette rightly assumed that Indian men want close shaves, as men across the world do, but the difference is that they do not place a premium on time. They spend up to 30 minutes shaving, whereas U.S. men spend five to seven minutes.

To come up with a competitive product, Gillette had to relearn the science of shaving with a single blade. It found that multiple passes of a single-blade razor can achieve a close shave because of the viscoelastic nature of hair. As a blade cuts strands of hair, it also pulls them out a little from the skin. The hairs don’t spring back at once; the follicles act like the mechanisms that close a screen door slowly. Because the hairs continue to protrude, the next pass of the blade can cut them a little shorter. And so on.

This process helped Gillette hit upon a valuable design freedom: It could use only a single blade in its new razor, which drastically lowered the production cost. The new razor would also need 80% fewer parts than other razors did, greatly reducing manufacturing complexity.

Gillette’s engineers then had to figure out how to flatten the skin before cutting the hairs to ensure a close shave without injury. They also had to understand the mechanics of flushing out the razor by swishing it in a cup of water. Finally, they had to balance competing requirements: Small teeth at the cartridge’s front were necessary to flatten the skin before it made contact with the blade, while the rear had to have an unobstructed pass-through to allow hair and shaving cream to wash out easily.

Rethinking the razor from the ground up, the Gillette team also designed a unique pivoting head. That helped the user maneuver around the curves of the face and neck, particularly under the chin—an area difficult to shave. Seeing that Indians gripped razors in numerous ways, Gillette created a bulging handle and textured it to prevent slippage.

Gillette didn’t stop at designing a product specifically for India; it also built a new business model to support it. To reduce production and transportation costs, it manufactures the product at several locations. And because India’s distribution infrastructure consists of millions of mom-and-pop retailers, the team designed packaging that consumers could easily spot in any store.

Over time the American company did well in this Indian segment—mainly because it didn’t set out to make the cheapest razor; it strove to make a product with superior value at an ultralow cost. The Gillette Guard razor costs Rs 15 (around 25 cents)—3% as much as the company’s Mach3 razor and 2% as much as its Fusion Power razor—and each refill blade costs Rs 5 (8 cents). Introduced in 2010, the innovative product has quickly gained market share: Two out of three razors sold in India today are Gillette Guards. Although Gillette has not sold the Guard outside India yet, it embodies the promise of a successful reverse innovation.

Though most Western companies know that the business world has changed dramatically in the past 15 years, they still don’t realize that its center of gravity has pretty much shifted to emerging markets. China, India, Brazil, Russia, and Mexico are all likely to be among the world’s 12 largest economies by 2030, and any company that wants to remain a market leader will have to focus on consumers there. Chief executives have no choice but to start investing in the infrastructure, processes, and people needed to develop products in emerging markets. Doing so will also allow multinationals to benefit from the “frugal engineering” (as Renault’s CEO Carlos Ghosn labeled it) that’s possible there. Because of abundant skilled talent—especially engineers—and relatively low salaries in those countries, the costs of creating products there are often lower than in developed nations. But no amount of investment will result in portfolios of successful new products and services if companies don’t follow the design principles that govern the development of reverse innovations.

View at the original source

![[PCソフト] Windows 10 Enterprise Version 1607 (Updates Jul 2016)](http://i.imgur.com/vJg3vh9.jpg)